Welcome

Transformers are a type of sequence to sequence model, i.e., given a sequence of characters, which may be split into words, transformers are able to convert that sequence to another sequence in a way that preserves the original sequence's 'meaning' without using any predefined rules. An example of a sequence-to-sequence task is text translation, such as converting the English sentence "I ate an apple" into the Italian equivalent: "Ho mangiato una mela."

Transformers are an example of an encoder-decoder architecture. Encoder-decoder architectures take input data, squeeze it into a kind of secret code (often called 'creating a latent representation'), and sometimes decode the squeezed data to perform useful tasks. An example of an encoder-decoder architecture and a task it may be used on would be using an autoencoder to denoise images.

This page contains an implementation and demonstration of the transformer architecture from scratch using as few predefined libraries as possible in order to give the reader an understanding of what really goes on in each step of the process. We avoid using predefined models or implementations of algorithms as much as possible.

Introduction

We address the following questions:

- What is the fundamental principle of a transformer?

- In very general terms, what does a transformer do?

- What specific tasks do we need to do in order to implement a transformer?

1. What is the fundamental principle of a transformer?

The fundamental principle of a transformer is that one-hot vectors can be used to look up particular rows of a matrix, and you can exploit this to selectively extract, combine, and mask information from your input to produce better outputs1. A lot of readers, especially NLP enthusiasts, may immediately have a problem with this statement. After all, we have not used the most famous term associated with a transformer (attention) while stating this fundamental principle. We also did not say anything about feature embeddings, long-range dependencies, contextual relationships, and encodings - all terms that are used when talking/reading about transformers. This is done for two reasons. First, I believe that it is extremely important to understand what exactly is going on in terms of as many elementary operations as possible. I believe that this necessarily precludes using domain-specific jargon. Second, I am tired of reading innumerable blogs2, code comments on GitHub3, and slides that fail to give you understanding4.

2. In very general terms, what does a transformer do?

A transformer takes in a sequence of elements (this sequence is often long), figures out how different elements in that sequence are related, then squeezes that sequence into a list of numbers that capture any inherent 'meaning'5. It then takes that list of numbers and unsqueezes it into a different sequence that tries to preserve the 'meaning' of the original sequence. As shown in the welcome section, transformers can be used for language translation.

3. What specific tasks do we need to do in order to implement a transformer?

- Figure out a way to split individual elements in a sequence (hereafter 'words and punctuation in a sentence') and find a way to feed them to the computer.

- Make the computer squeeze these words into a list of numbers it can understand.

- Make the computer unsqueeze the list of numbers into words and form sentences in another language.

If you angrily clicked on the footnote after reading this sentence, are you an NLP enthusiast?

This is almost certainly me being lazy/not having any formal training in deep learning, but there is an awful lot of garbage out there, and most of it from full-time machine learning engineers! If I read another variation on 'Transformers have revolutionized the field of natural language processing by leveraging the attention mechanism to embed data and make better predictions'....

The better commented implementations of transformers from scratch that I found were created in 2024. Does this say anything about the field of machine learning?

Slides are often combined with lectures, so I am willing to give this one a pass. They are also often meant for explaining new things to people who already have experience in the field, so it makes sense that I wouldn't understand them. Unsurprisingly: https://sites.astro.caltech.edu/%7Egeorge/ay141/mermin.pdf

As of 2024, anyone claiming that transformers/LLMs can understand and reason like humans is pontificating.

Preliminaries

Suppose our input language only has four words ('My', 'rabbit', 'likes', 'bananas'), and no punctuation at all. Sentences from our language could be 'rabbit likes bananas' or 'My rabbit likes bananas' or 'likes My bananas' or 'bananas rabbit My'. For the sake of sanity, let's assume that our language only has the sentence 'My rabbit likes bananas'. We want to translate this into Italian: 'Al mio coniglio piacciono le banane'. How do we feed our initial sentence to a computer?

Tokenization

We first need to split the sentence into individual words. Because our language does not have any sort of punctuation, we can do what is called whitespace tokenization. This is the most natural way of splitting an English sentence - assume that individual words are separated by a blank space, read through the sentence, and store all characters between two whitespaces as a single word 1.

Obviously, this goes wrong the instant you add punctuation, have strings like 'abcdefghijklabcabcdabcdeab' as input, have more words than your input stream can handle, and so on. However, implementing byte-pair encoding would go beyond the scope of the tutorial.

from typing import List #for clean function annotation

def whitespace_tokenizer(sentence: str) -> List[str]:

"""

Function that reads a string/sentence and outputs a list of strings, where each output string is a word in that sentence. Each word is considered to be delimited by whitespaces.

Input:

sentence: str - assumed nonempty for explanation purposes

Output:

list of strings

"""

tokenized_sentence=[] #final output, a list of words

current_word=[] #list to store the current word

#The technique to whitespace tokenize the sentence is to iterate through it, and store each non-whitespace character in current_word.

#Once a whitespace is encountered, append the contents of current_word to tokenized_sentence and clear current_word

for i in sentence:

if i==" ":

if current_word:

tokenized_sentence.append(''.join(current_word)) #append to the list of tokens

current_word=[]#reset current_word

else:

current_word.append(i)

#this still leaves the final word in, so add it last

if current_word:

tokenized_sentence.append(''.join(current_word))

#delete the current word from memory explicitly (not required)

del current_word

return tokenized_sentence

english_sentence="My rabbit likes bananas"

print("Your list of tokens for the English sentence is:", whitespace_tokenizer(english_sentence))

english_tokenized_sentence=whitespace_tokenizer(english_sentence) #save the tokenization in a list

italian_sentence="Al mio coniglio piacciono le banane"

print("Your list of tokens for the Italian sentence is:", whitespace_tokenizer(italian_sentence))

italian_tokenized_sentence=whitespace_tokenizer(italian_sentence)

Your list of tokens for the English sentence is: ['My', 'rabbit', 'likes', 'bananas']

Your list of tokens for the Italian sentence is: ['Al', 'mio', 'coniglio', 'piacciono', 'le', 'banane']

Feeding these words to a computer

How do we feed these words into a computer? One way of doing it would be by assigning each individual word to a real number: ['My', 'rabbit', 'likes', 'bananas'] -> ['935.88', '-28124.4483957', '3', '-2']. This is inefficient, as the amount of precision you would need to implement would increase computatational costs and storage requirements. A better way of storing a word would be to store it in a vector. Here is how we can do this. Given a vector, stored as a column matrix with rows, where is the number of words in your vocabulary, replace one of the zeros with 1 such that the position of the 1 is unique for that particular word. Then, stack those vectors side by side to form a matrix where each row and column has only one 1 and all other elements are zero. Such vectors are called 'one-hot' vectors and this is a type of encoding called one-hot encoding.

This is illustrated below:

'My'=, 'rabbit'=, 'likes'=, 'bananas'=, 'My rabbit likes bananas'=

Let's call the last matrix , for 'word matrix'. Observe that when any one-hot encoded is multiplied with another matrix, by the rules of matrix multiplication, the column of the second matrix corresponding to the position of the 1 in the column vector is 'pulled out'1. This is illustrated below:

If you're able to construct this second matrix, then it can potentially lead to something interesting2. There are of course other ways to encode words, and for practical language tasks you take someone else's encoding and use it, but it is important to understand the core principle.

I have transposed the column vector to make it a row vector.

Foreshadowing

import numpy as np

from typing import List, Dict, Tuple

import random

def create_concatenated_matrix_from_tokens(tokens: List[str]) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Function that creates a concatenated one-hot encoded matrix from a tokenized sentence.

Input:

tokens: List containing tokens

Output:

tokenized_matrix: A 2-D one-hot encoded np.ndarray of tokens. Each row and column contains only one 1. Always square.

"""

#The idea is to simply generate a diagonal matrix which will be one-hot encoded by definition

#Create a dictionary to map each token to a unique index

token_to_index={token: idx for idx, token in enumerate(tokens)} #get index-token pair from the input list

#Initialize the matrix with zeros

tokenized_matrix=np.zeros((len(tokens), len(tokens)), dtype=int)

#Populate the one-hot encoded matrix

for token in tokens:

index=token_to_index[token]

tokenized_matrix[index][index]=1 #Set the diagonal element to 1

return tokenized_matrix, token_to_index #this second variable is returned to pull out a random token and corresponding vector later

english_onehot_matrix, english_token_to_index=create_concatenated_matrix_from_tokens(english_tokenized_sentence)

print("The English one-hot encoded matrix is:\n", english_onehot_matrix)

#let's pull out a random token and a one-hot encoded vector to see how it pulls out specific features

def get_random_token_and_vector(token_to_index: Dict[str, int], one_hot_matrix: np.ndarray) -> Tuple[str, np.ndarray]:

"""

Function that pulls a random token and its corresponding one-hot vector.

Input:

token_to_index: Dictionary mapping tokens to their indices

one_hot_matrix: 2D NumPy array containing one-hot vectors

Output:

A tuple containing the random token and its corresponding one-hot vector

"""

#Randomly select a token

random_token=random.choice(list(token_to_index.keys()))

#Get the corresponding one-hot vector

one_hot_vector=one_hot_matrix[token_to_index[random_token]]

return random_token, one_hot_vector

random_token, corresponding_one_hot_vector=get_random_token_and_vector(english_token_to_index, english_onehot_matrix)

print("Let's pick a random token:", random_token, "\nThe corresponding one-hot vector is:", corresponding_one_hot_vector)

#generate a random matrix to demonstrate pulling out certain columns/rows

random_matrix=np.random.rand(len(english_tokenized_sentence), len(english_tokenized_sentence))

print("Multiplying an example random matrix\n", random_matrix, "\nby", random_token+"'s one-hot vector", corresponding_one_hot_vector, "\npulls out the row", np.matmul(corresponding_one_hot_vector, random_matrix), "\nand multiplying by the tranpose of that vector pulls out the column:\n", np.matmul(random_matrix, corresponding_one_hot_vector[:, np.newaxis]))

The English one-hot encoded matrix is:

[[1 0 0 0]

[0 1 0 0]

[0 0 1 0]

[0 0 0 1]]

Let's pick a random token: bananas

The corresponding one-hot vector is: [0 0 0 1]

Multiplying an example random matrix

[[0.48871169 0.52574402 0.78833029 0.7045616 ]

[0.76188795 0.13720883 0.39406852 0.02774654]

[0.27090269 0.35964049 0.20715361 0.3064574 ]

[0.23701048 0.67718606 0.87441259 0.05116356]]

by bananas's one-hot vector [0 0 0 1]

pulls out the row [0.23701048 0.67718606 0.87441259 0.05116356]

and multiplying by the tranpose of that vector pulls out the column:

[[0.7045616 ]

[0.02774654]

[0.3064574 ]

[0.05116356]]

Sequence prediction

An immediate application of this specific kind of matrix multiplication is as follows. Suppose we have the following sentence in our four-word language: 'My rabbit'. Our task is to predict the next word that comes after it1. One easy way of doing this is by observing that we only have four options. We can construct the following four sentences:

| Next Word | Potential next (possible incomplete) sentence |

|---|---|

| My | My rabbit My |

| rabbit | My rabbit rabbit |

| likes | My rabbit likes |

| bananas | My rabbit bananas |

How do we decide what word comes next? Well, we can't decide on our own. Perhaps, to an alien whose language consists of only four words that sound exactly like English words, the sentence 'My rabbit My' would translate to English as 'I am in need of two oranges and a deck of playing cards.' The sentence 'My rabbit rabbit' would translate to 'I am on fire'. The sentence 'My rabbit rabbit rabbit rabbit bananas bananas rabbit bananas My likes likes bananas' would translate to 'Yes' (remember, I have not put any limits on the length of the sentences!). The point of these examples is to show you that there is no way for us to predict the next word unless we have some idea of what it is going to be. One way to solve this problem is for a third party (say a talking dog) to step in and say, "I've been around these aliens, and I've observed that whenever they begin a sentence with 'My rabbit', the next word is 'bananas' 10% of the time, 'likes' 85% of the time, 'rabbit' 5% of the time, but 'My' never comes after 'rabbit'. Is there some way for you to use this information? Also, whatever I say is always true."

Since we have no better option, let's trust the talking dog. We can in fact use its information in the following way. We can construct the following vector that shows the probability of predicting the next word after 'rabbit', if spoken by an alien.

This is somewhat useful. We know that there is a high chance that the next word in the sentence will be 'likes', so the possible incomplete sentence will now probably be 'My rabbit likes'. But wait a minute. This vector of probabilities is like the column we pulled out of the matrix above. Is it possible to reconstruct this matrix? We can certainly do so - just assume that the dog is always true and start interrogating the dog about the probabilities of the next word after each word in the language, regardless of the context. Let's assume the dog is happy to tell us this, so we now have the following matrix:

The matrix is read row-first, column-second i.e. the probability that the word 'likes' occurs after 'rabbit' is 0.85.

This tells us something about how the language is constructed. We know that if we hear an alien say 'rabbit', there is a very high chance that it will say 'likes' next. If we hear it say 'likes', there is a very high chance it will say 'bananas' next. There is also a very small chance it will say 'My' after 'likes', but it will never say 'likes' after 'likes'. Therefore, to a first order, we can construct this matrix of probabilities that tells us what the next word in the language is going to be. In more formal terms, this is the stochastic matrix of a first-order Markov chain. It is first-order because the next word in the language only depends on the current word of the language.

But wait. Languages tend to have meaning when several words are used together. For example, in English, the word 'cold' refers to something whose molecules have a lower average kinetic energy than a reference object. However, the phrase 'cold call' means unsolicited phone calls typically made for business purposes. If you only know that the current word in the sentence is 'cold' and your probability matrix says that the word 'call' appears after 'cold' 70% of the time, you may say that the sentence 'The water is cold.' is incomplete and would complete it by saying 'The water is cold call.', which makes no sense2. What do we do?

The natural approach is to say, "I know combinations of words tend to change the meaning of a phrase3, but I don't have any idea what constitutes a phrase in my unknown language, nor do I know if the 'meaning' of the sentence itself changes if a two words are present in adjacent positions4. Let me do the same thing I did for my first-order Markov chain. Instead of asking the talking dog the probabilities of the next word after my current word, I will look at the probabilities of the next word after my current word if another word is present in the sentence."

Specifically, you can ask the talking dog the questions "If 'rabbit likes' is present in the sentence, what is the probability that the next word is 'bananas'? What about 'rabbit', 'My', and 'likes'? If 'My rabbit' is present, what is are the probabilities for the next word?" and construct the same matrix as we did above. Since we are looking at every pair of words, the number of rows of the matrix quickly grows in size. If there are 5 words in the language, the number of two-word pairs is 20 (obtained from ) since the order matters. If there are 100 words, there are 4950 pairs. If there are 260,000 words (a quick Google search tells me that this is roughly the number of words in Italian) then there are 33799870000 pairs. And this is just for consecutive word pairings! If we attempt to look even further back i.e. three-word pairs, there will be even more. It is easy to see that the amount of space required to store this prediction matrix grows exponentially5.

Given a sufficiently large prediction matrix containing all possible words and combinations of all possible lengths, we are able to predict the next word. Note that we have not said anything about actually choosing the next word in this situation, as this leads to problems. One problem is that we still do not know how to deal with cases where there is an equal chance of two words appearing after our current word. Let's ignore this for now and focus on the biggest one: We want to avoid actually constructing any such matrix. Let's try another trick. Let's say, "The next word in a sentence is easier to predict if another word appears before the current word, but not necessarily directly before it. It may happen sometimes, but there is no reason why it should be like this. Here is my hypothesis. I think that it is easier to predict the next word in the sentence given a probability matrix containing all possible combinations of words where the second word is the current word." This would look something like:

This is much better to work with. Note that this is no longer a representation of a Markov chain, as we cannot simply look at the row corresponding to the current word and predict the next one. What can we do instead? We can say: "Okay, let's say that these probabilities represent how much these pairs contribute to the next word in the sequence. We call these probabilities as votes and to predict the next word, we can sum over each column and compare these sums to determine the next word." This is good, because now we are capturing long-range/skip dependencies in the language/sequence. Each row now represents one of many features that can describe our sequence at a particular point.

This is more clearly illustrated when you have, say, only two possible sentences in the language, but the main takeaway from actually doing this task for a set vocabulary and finite amount of sentences in the language is the observation that many elements in this probability matrix do not matter. They can either be so small that they are practically zero, or something like 0.5, which means that the next word is equally likely to appear regardless of the sentence, so it may not matter too much. What we are really interested in are elements we can distinguish. For example, suppose that the two sentences that were possible in our language were 'My rabbit likes bananas' and 'My bananas likes rabbit'. If we had the incomplete sentence 'My rabbit likes', then we could ask the talking dog to give us this matrix, and what we would see is that the matrix has a large number of zeros but a 1 for 'bananas', enabling us to do this sum-over-columns technique to accurately predict the next word, even with a deep dependency. To be fair, this example is a bit contrived and longer sentences would illustrate the point much more easily.

This is still pretty bad. Real languages have a large number of words. Our talking dog could have only been around aliens who lived on a certain continent of the alien planet, which led to them developing their own dialect. If you think about it for just a little bit, it is easy to see that this sum-over-columns approach can end up telling us that the next word in the incomplete sentence 'Japan is east of' can be 'China', with a vote total of 2339, and 'Mongolia', with a vote total of 2340. Sure, we can still pick 'Mongolia' as the next word, but such a small difference can naturally be induced by statistical noise, unknowingly biased probability matrices, and other factors (such as us messing up the addition!). Are there ways to overcome this?

One approach is to modify the values in the columns before you sum them up, in a way that allows us to differentiate between them even more. One way to do this is to simply sum all the values and divide each value by the sum, to get a fractional representation. This is not very helpful - it preserves the same relation between the numbers in terms of scaling. Converting a column of [1,2,3] to [0.1666, 0.3334, 0.5] preserves the scaling. To overcome this, we utilize the independence from irrelevant alternatives axiom of decision theory, which states that irrelevant choices should not affect the relative probability of choosing between the things you really want to choose between. In mathematical terms, this means that if you have a set of numbers and you want to decide between and but are small values that are affecting your confidence, you can suppress by replacing each variable in the following way:

This is the famous softmax function which is more or less used to convert a probability distribution to another probability distribution6. The important thing is that the softmax function suppressed irrelevant values (as as ).

However, the softmax function is also not applicable to our scenario. Suppose we did actually end up converting the votes to a probability distribution and summing them. What would it actually look like? Let's do an example below:

The sum of the softmaxed vector elements is 1. This is correct, because we did just convert it to a probability distribution. So this approach, while it did 'suppress' the smaller values, does not actually help us with voting. What can we do?

"Okay," we say. "Let's do something else. Instead of attempting to modify every value, let's just discard the values that aren't important7. First, let's look at how to extract specific features from our matrix. We know one-hot encoded vectors pull relevant rows/columns out of the matrix, so let's make a one-hot encoded vector to pull out the relevant features in the matrix in the following way. We construct a vector initially filled with zeros featuring all possible pairs in sentence where the second word is the current word, and the first word has all other words (possibly including the current word, depending on the dimensions of our matrix). Then, if the first word appears before the current word in the sentence, set that element to 1. This vector allows us to pull out the features of our probability matrix that are 'active' until that current point."

This would look like:

Note the transpose sign. We can see that the matrix multiplication will suppress those elements in the pulled out feature vectors where pairs taking into account words appearing after the current word in the sequence will be suppressed i.e. we cannot use knowledge of the entire sentence to predict the next sentence. We have now 'suppressed the future', but we still need to figure out what feature elements in our sequence are important. This is still an unknown, but what we can do is use another one-hot encoded vector to multiply this suppressed vector, to suppress even more. That is: we can compute the pairwise product to return a vector after multiplying our two vectors. Where can we get this second one-hot encoded vector? Let's assume that the talking dog gave this to us. The point is that if we manage to suppress information then our voting becomes much stronger, as a lot of elements will be 0. The trick is now to find out how to create this second vector so that we suppress irrelevant information.

Incidentally, the second form of suppression is the idea behind attention.

In the sense that the next word is 'meaningful'.

I am deliberately including punctuation here, as the same technique can be used when punctuations are treated as unique words.

This is also partially the reason the appeal to etymology is incorrect.

Compare 'hot', 'dog', and 'hot dog'.

Foreshadowing

Technically, this is what we have been attempting to do this entire time.

import numpy as np

from typing import List, Dict, Tuple

import random

#remember that the english sentence is "My rabbit likes bananas"

def generate_biased_probability_matrix(size: int) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Function to generate a square probability matrix where each row and column

has one value significantly higher than the others.

Input:

size: The number of rows and columns in the square matrix

Output:

biased_matrix: A 2-D np.ndarray where each row and column has one high-probability value

"""

#the technique is to generate a uniform matrix and randomly assign biased high probability values in each row and column

biased_matrix=np.random.uniform(0.01, 0.05, (size, size))

#generate high probability values for each row and column

high_probabilities=np.random.uniform(0.7, 0.9, size=size)

#ghuffle indices to randomly distribute the high probabilities across columns

indices=np.arange(size)

np.random.shuffle(indices)

#assign one high probability per row and column

for i in range(size):

biased_matrix[i, indices[i]]=high_probabilities[i]

#normalize each row to sum to 1

biased_matrix=biased_matrix/biased_matrix.sum(axis=1, keepdims=True)

return biased_matrix

size=4

example_probability_matrix=generate_biased_probability_matrix(size)

print("As an example, a second-order probability matrix with skip dependencies given to us by the talking dog can be this:")

print(example_probability_matrix)

def softmax(numbers: List[int])->List[int]:

"""

Function to softmax a set of numbers

Input:

numbers: a list of integers

Output:

The list, softmaxed

"""

exponential_list=np.exp(numbers)

softmaxed_numbers=[np.exp(number)/sum(exponential_list) for number in numbers]

return softmaxed_numbers

def digram_one_hot_encoding(sentence: str, tokens: List[str], index_of_word: int) -> Tuple[np.ndarray, np.ndarray]:

"""

Generate one-hot encoding vectors for digrams based on a user-defined index.

Input:

sentence: Original sentence (used for context if needed).

tokens: List of words (tokens) in the sentence.

index_of_word: Index of the target word in the tokens list. Zero-indexed

Output:

A tuple containing:

- A NumPy array of digrams (other words paired with the target word).

- A 1D NumPy array where each element is 1 if the other word appears before the target word, 0 otherwise.

"""

if index_of_word<0 or index_of_word>=len(tokens):

raise ValueError("Invalid user-defined index. Must be within the range of the tokens list.")

#extract the target word. This of course assumes that the tokenization is sequential, but for illustrative purposes, it is fine

target_word = tokens[index_of_word]

#generate digrams and the one-hot vector. The idea is that if the word appears before our word then set the index to 1, else 0

digrams=[f"{token},{target_word}" for idx,token in enumerate(tokens) if idx!=index_of_word]

one_hot_vector=np.array([1 if idx<index_of_word else 0 for idx in range(len(tokens)) if idx!=index_of_word],dtype=int)

return np.array(digrams), one_hot_vector

print("Our sentence is:", english_sentence)

#lets take index 2 ('likes' in "My rabbit likes bananas")

index_of_word=2

incomplete_sentence=" ".join([word for index,word in enumerate(english_tokenized_sentence) if index<index_of_word+1])

print("We want an incomplete sentence. Our generation task is to predict the next word in:", incomplete_sentence)

#generate the digrams (word pairs)

digrams,digram_onehot_vector=digram_one_hot_encoding(english_sentence,english_tokenized_sentence,index_of_word)

print("Digrams:")

print(digrams)

print("One-hot vector (without any future dependency):")

print(digram_onehot_vector)

#next, we create the attention mask by hand. specifically, we generate a ones vector equal to the size of the number of words in our sentence

#then we randomly pick 2

attention_mask=np.ones((len(whitespace_tokenizer(incomplete_sentence))), dtype=int)

zero_indices = np.random.choice(len(whitespace_tokenizer(incomplete_sentence)), size=random.randrange(0,len(whitespace_tokenizer(incomplete_sentence))), replace=False)

attention_mask[zero_indices]=0

print("Example attention mask: ", attention_mask.T)

print("Attention applied to the non-future dependency capturing one-hot vector:", attention_mask*digram_onehot_vector)

As an example, a second-order probability matrix with skip dependencies given to us by the talking dog can be this:

[[0.03888508 0.03133871 0.88147493 0.04830127]

[0.89819378 0.03108927 0.03605569 0.03466125]

[0.02927141 0.88815681 0.02795252 0.05461926]

[0.01763851 0.04167578 0.05967272 0.881013 ]]

Our sentence is: My rabbit likes bananas

We want an incomplete sentence. Our generation task is to predict the next word in: My rabbit likes

Digrams:

['My,likes' 'rabbit,likes' 'bananas,likes']

One-hot vector (without any future dependency):

[1 1 0]

Example attention mask: [0 0 1]

Attention applied to the non-future dependency capturing one-hot vector: [0 0 0]

What attention does

We have so far our non-future dependent feature vector. We have used it so far in conjunction with the probability matrix to predict the next step. If we want to suppress the feature vector with attention, does it make sense to use another matrix in the same way? Let's assume that we have a bunch of attention masks/vectors. We can stack them either vertically or horizontally (depending on how exactly we want to implement our lookup) and generate a matrix of attention masks. We can then send our feature vector through the attention matrix and then send the result of that product into our probability matrix to predict the next word.

def send_vector_through_two_matrices(vector: np.ndarray, probability_matrix: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Function to send an input vector through an attention matrix and then a probability matrix

Inputs:

vector: a 1D NumPy ndarray

Output:

a 1D NumPy ndarray of the same length as the input after being sent through two matrices

"""

#the idea is to generate a 1d array of ones, replace half of the elements with 0, and shuffle and reshape it

print("Your input vector is:\n", vector)

total_elements=vector.shape[0]**2

half=total_elements//2

flat=np.ones(total_elements, dtype=int)

flat[:half]=0

np.random.shuffle(flat)

example_attention_matrix=flat.reshape((vector.shape[0],vector.shape[0]))

print("An example attention matrix is:\n", example_attention_matrix)

result_1=np.matmul(vector, example_attention_matrix)

print("After multiplying, you get:\n",result_1)

print("After multiplying the result with the probability matrix, you get", np.matmul(result_1, probability_matrix))

example_probability_matrix=np.random.rand(len(digram_onehot_vector), len(digram_onehot_vector))

print("An example probability matrix is:\n", example_probability_matrix)

send_vector_through_two_matrices(digram_onehot_vector, example_probability_matrix)

An example probability matrix is:

[[0.6600921 0.31488209 0.01236613]

[0.51302175 0.04638934 0.92027961]

[0.38042472 0.01756476 0.29279993]]

Your input vector is:

[1 1 0]

An example attention matrix is:

[[1 1 0]

[1 0 1]

[0 0 1]]

After multiplying, you get:

[2 1 1]

After multiplying the result with the probability matrix, you get [2.21363067 0.69371827 1.2378118 ]

Reconstructing word pairs from encoded vectors

What do we do with the result of the attention step? Sure, we have a vector that has encoded word pairs (a second-order model), but we don't yet have a way to deconstruct that vector back into a word pair. How do we do this? So far, matrix multiplication has enabled us to encode sentences into vectors and selectively mask the irrelevant word pairs. Can we apply matrix multiplication to decode a word pair? The answer is yes. Matrix multiplications are in fact what neural networks do.

Neural Networks

Neural networks are a deep learning architecture based on the neuron-synapse structure of the human brain. Neural networks consist of a series of blocks called artificial neurons (hereafter just 'neuron') stacked vertically in layers. Each neuron has the possibility to receive an input and pass along an output to another neuron. To decide whether it passes along an output, a neuron sums up all of its inputs (which are weighted by the value of the connection along which the output travels) and applies a function, called an activation function, to that sum. Depending on the result of the activation function, the neuron sends an output to one or more neurons depending on how many it connects to. Mathematically, passing data through a neuron is equivalent to applying the mathematical function , where is the activation function, is the weight along an input path, and the actual value being sent along that input path.

Neural networks are equivalent to matrix multiplication. Why is this so? Suppose there are two layers in our neural network. The first layer has 3 neurons, and the second layer has two neurons. Let's name the latter two and . Also, let's assume that each neuron in the first layer sends is connected to each neuron in the second layer. Therefore, the outputs of the first layer are and the weights of the paths along which they are sent are for each neuron-neuron path.

The input to is , and the input to is . Writing these out in the form of a system of linear expressions:

it is easy to see that this is in fact a matrix multiplication:, where . Each layer also tends to have a bias term, so the input to a layer can be represented as the equation , where is the bias matrix (usually a column vector containing the same value). The activation function is applied to this resultant vector. This means that the output of a layer of a neural network can be represented by a vector.

Properties of neural networks

- Neural networks are universal function approximators. This means that given a large-enough network with nonlinear activation functions, neural networks can model any mapping between elements of a domain and a codomain . However, this does NOT tell us how many neurons and layers we need or what the activation function is.

- Neural networks can model nonlinear relationships between elements. While the discussion of linear decision boundaries is beyond the scope of this tutorial, it is enough to know that , the activation function, is usually chosen to be something like ReLU or the sigmoid function.

- Since neural networks are just matrix multiplication, they are extremely fast to train on computers1

Activation functions

If the activation function is linear (such as a simple multiplier ), the neural network cannot learn linear relationships, no matter how big you make it and how long you train it for. Nonlinear activation functions are necessary to learn nonlinear relationships i.e. relationships between two variables that cannot be explained by a matrix multiplication (attention is linear!). Activation functions like ReLU and the sigmoid function are chosen not only because they are easy to compute, but because of a certain requirement explained below.

Training a neural network

Since each layer of a neural network can be expressed as a function , a neural network can be thought of as a large composite function . Given a training set of pairs, the loss of the model is a cost function where is the prediction of the neural network (the large composite function defined above) for the input variable . We want to minimize this cost function, as it means our neural network has learned the relationship between the input and output variables. This is done with an algorithm called backpropagation.

Backpropagation is an algorithm that utilizes the technique of gradient descent - given a cost function, we calculate its gradient with respect to the weights and biases of the neural network. According to the learning rate , gradient descent updates the weights and biases of the neural network according to the rule

where is read as 'OR'. We subtract the gradient because the gradient denotes the direction of maximum increase, so the direction of maximum decrease would be the direction opposite to it. We apply this many times (this is therefore a greedy algorithm) to find the local minimum of the function i.e. the values of all and all where the cost function is minimized. After each step of updating the gradients, we have to compute the prediction of the network again, in order to prepare for the next step. This is called the forward pass or forward step through the network, and must be computed repeatedly, making the process a back-and-forth.

Calculating backpropagation

Let us consider a neural network set up in the following way. We have 3 input neurons (that is, 3 input variables) and 1 hidden layer with 4 neurons, and one output neuron. For the sake of this example, assume that every neuron in one layer is connected to every neuron in the next layer and every neuron in the previous layer. Such a neural network is called a fully-connected neural network.

We have already seen how matrices can represent the input to a layer. Let's represent the output of a layer by a vector after an activation function is applied to each neuron2. We will now define several variables that mathematically represent each layer. For each layer , we have:

We can write down some straightforward formluae after these definitions.

The next question is choosing an appropriate cost function for our task. Let us think about our task for a moment. Since we have been using probabilities all along to predict the next word in our sequence, it is appropriate to use a cost function that tells us how good our probability prediction is. The classical cost function that is used to explain backpropagation is the squared error function, . This function is natural because it is simply the difference between what we predict and what the truth is, and it is squared for many reasons such as being the variance of the unbiased estimator (if used in its mean-square form) and also being easily differentiable3. But we effectively want to measure the difference between a predicted probability distribution and the real probability distribution, as we are predicting the next word in a sentence. This requires having a maximum likelihood estimate of the parameters, and when working with Bernoulli-distributed variables (such as one-hot encoded vectors) the cross-entropy loss function minimizes the maximum likelihood estimate4.

Let's see how the derivative is calculated.

by a simple application of the chain rule. This can easily be extended by observing that is a function of , which is a function of , and is a function of .

and similarly for the first (input) layer, named layer 0.

The next task is setting up a way to recursively calculate the derivative of the cost function for any arbitrary layer's weight and bias. The general equation for this is

There are two observations we can make from this. The first is that it is straightfoward to numerically calculate the partial derivative for the last/output layer, and we can store this value in order to avoid repeated computation wherever possible. The second is that you need to calculate the change in the gradient for the last layer, then use that changed gradient for the layer before that one, and so on, 'back-propagating' the errors.

Let's choose a nice activation function such as the sigmoid function for this. Let us precompute the partial derivative of the output layer, since we'll be needing it. Note that denotes the Hadamard, or element-wise product.

This is a very nice result. It is now easy to see that for any inner layer, we can repeatedly apply the chain rule to derive the partial derivatives. If you go about doing this you end up with the following results:

A more complete derivation can be found here5, but the fundamental idea is the same.

We can now implement this in Python and train the neural network from scratch.

For this reason, layers tend to have the same activation function, as it is easy to parallelize the computation

Making automatic differentiation easier led to the invention of many fundamental inventions in empirical learning

https://sacred-texts.com/hin/m01/m01002.htm, 'I am (continued Sauti)...'

"""

Neural Network Implementation in NumPy

Inputs:

None

Outputs:

Fully functional neural network trained on synthetic data

"""

import numpy as np

def sigmoid(x: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Apply the sigmoid activation function element-wise

Inputs:

x: a NumPy ndarray, the input array

Outputs:

a NumPy ndarray with sigmoid applied element-wise

"""

return 1/(1+np.exp(-x))#sigmoid formula

def sigmoid_prime(x: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Compute the derivative of the sigmoid function element-wise

Inputs:

x: a NumPy ndarray, the input array

Outputs:

a NumPy ndarray with the derivative of sigmoid applied element-wise

"""

return sigmoid(x)*(1.0-sigmoid(x))#sigmoid derivative formula

class NeuralNetwork:

"""

Define a simple feedforward neural network

"""

def __init__(self,architecture: np.ndarray):

"""

initializer for the neural network class

Inputs:

architecture: a NumPy array representing the number of neurons in each layer

"""

self.L=architecture.size-1#number of layers (excluding input layer)

self.n=architecture#number of neurons in each layer

self.parameters={}#dictionary to store weights, biases, and activations

#initialize weights and biases for each layer

for i in range(1,self.L+1):

self.parameters['W'+str(i)]=np.random.randn(self.n[i],self.n[i-1])*0.01#small random weights

self.parameters['b'+str(i)]=np.ones((self.n[i],1))#biases initialized to 1

self.parameters['z'+str(i)]=np.ones((self.n[i],1))#pre-activation values initialized to 1

self.parameters['a'+str(i)]=np.ones((self.n[i],1))#activations initialized to 1

self.parameters['a0']=np.ones((self.n[0],1))#input layer activation

self.parameters['C']=1#placeholder for cost value

self.derivatives={}#dictionary to store derivatives

def forward_propagate(self,X: np.ndarray):

"""

Perform forward propagation

Inputs:

X: a column vector representing one training example

Outputs:

None

"""

self.parameters['a0']=X#set input layer activation

for l in range(1,self.L+1):

self.parameters['z'+str(l)]=np.dot(self.parameters['W'+str(l)],self.parameters['a'+str(l-1)])+self.parameters['b'+str(l)]#W*a+b

self.parameters['a'+str(l)]=sigmoid(self.parameters['z'+str(l)])#apply sigmoid activation

def compute_cost(self,y: np.ndarray):

"""

function to compute the cost for one training example

Inputs:

y: the true label for the input sample

Outputs:

None

"""

self.parameters['C']=-(y*np.log(self.parameters['a'+str(self.L)])+(1-y)*np.log(1-self.parameters['a'+str(self.L)]))#binary cross-entropy loss

def compute_derivatives(self,y: np.ndarray):

"""

function to compute gradients for all parameters

Inputs:

y: the true label for the input sample

Outputs:

None

"""

self.derivatives['dz'+str(self.L)]=self.parameters['a'+str(self.L)]-y#last layer gradient

self.derivatives['dW'+str(self.L)]=np.dot(self.derivatives['dz'+str(self.L)],self.parameters['a'+str(self.L-1)].T)#last layer weights gradient

self.derivatives['db'+str(self.L)]=self.derivatives['dz'+str(self.L)]#last layer bias gradient

for l in range(self.L-1,0,-1):

self.derivatives['dz'+str(l)]=np.dot(self.parameters['W'+str(l+1)].T,self.derivatives['dz'+str(l+1)])*sigmoid_prime(self.parameters['z'+str(l)])#hidden layer gradient

self.derivatives['dW'+str(l)]=np.dot(self.derivatives['dz'+str(l)],self.parameters['a'+str(l-1)].T)#hidden layer weights gradient

self.derivatives['db'+str(l)]=self.derivatives['dz'+str(l)]#hidden layer bias gradient

def update_parameters(self,alpha: float):

"""

function to update network parameters using gradient descent

Inputs:

alpha: learning rate

Outputs:

None

"""

for l in range(1,self.L+1):

self.parameters['W'+str(l)]-=alpha*self.derivatives['dW'+str(l)]#update weights

self.parameters['b'+str(l)]-=alpha*self.derivatives['db'+str(l)]#update biases

def predict(self,x: np.ndarray) -> np.ndarray:

"""

function to predict the output for a given input

Inputs:

x: a column vector representing one input sample

Outputs:

a NumPy array representing the predicted output

"""

self.forward_propagate(x)#perform forward propagation

return self.parameters['a'+str(self.L)]#return output layer activation

def fit(self,X: np.ndarray,Y: np.ndarray,num_iter: int,alpha: float=0.01):

"""

function to train the neural network

Inputs:

X: a NumPy array where each row is a training example

Y: a NumPy array of true labels

num_iter: number of iterations

alpha: learning rate

Outputs:

None

"""

for iter in range(num_iter):

c=0#cumulative cost

n_c=0#correct predictions count

for i in range(X.shape[0]):

x=X[i].reshape((X[i].size,1))#reshape input to column vector

y=Y[i]#true label

self.forward_propagate(x)#forward propagation

self.compute_cost(y)#compute cost

self.compute_derivatives(y)#compute gradients

self.update_parameters(alpha)#update parameters

c+=self.parameters['C']#accumulate cost

y_pred=self.predict(x)#make prediction

y_pred=(y_pred>0.5)#convert probability to binary

if y_pred==y:

n_c+=1#correct prediction count

c=c/X.shape[0]#average cost

print('Iteration:',iter)

print("Cost:",c)

print("Accuracy:",(n_c/X.shape[0])*100)

#generate synthetic data

np.random.seed(42)#reproducibility

X=np.random.rand(200,7)#200 samples, 7 features

y=(np.sum(X,axis=1)>3.5).astype(int).reshape(200,1)#labels based on sum of features

#split data into training and testing sets

split_ratio=0.7#70% training data

split_index=int(X.shape[0]*split_ratio)

indices=np.arange(X.shape[0])

np.random.shuffle(indices)

X_train,X_test=X[indices[:split_index]],X[indices[split_index:]]

y_train,y_test=y[indices[:split_index]],y[indices[split_index:]]

#define architecture

architecture=np.array([7,5,1])#7 input features, 5 hidden neurons, 1 output

#initialize and train the neural network

nn=NeuralNetwork(architecture)

nn.fit(X_train,y_train,num_iter=50,alpha=0.1)

#evaluate the model

correct_predictions=0

for i in range(X_test.shape[0]):

x=X_test[i].reshape((X_test[i].size,1))#reshape to column vector

y_true=y_test[i]#true label

y_pred=nn.predict(x)#prediction

y_pred=(y_pred>0.5).astype(int)#convert to binary

if y_pred==y_true:

correct_predictions+=1#count correct predictions

#calculate test accuracy

test_accuracy=(correct_predictions/X_test.shape[0])*100

print("Test Accuracy:",test_accuracy)

Iteration: 0

Cost: [[0.72566273]]

Accuracy: 64.28571428571429

Iteration: 1

Cost: [[0.71523798]]

Accuracy: 66.42857142857143

Iteration: 2

Cost: [[0.70509586]]

Accuracy: 66.42857142857143

Iteration: 3

Cost: [[0.6864599]]

Accuracy: 67.85714285714286

Iteration: 4

Cost: [[0.65347682]]

Accuracy: 75.71428571428571

Iteration: 5

Cost: [[0.60664836]]

Accuracy: 82.14285714285714

Iteration: 6

Cost: [[0.55558826]]

Accuracy: 91.42857142857143

Iteration: 7

Cost: [[0.5072171]]

Accuracy: 93.57142857142857

Iteration: 8

Cost: [[0.46296521]]

Accuracy: 95.0

Iteration: 9

Cost: [[0.42292781]]

Accuracy: 96.42857142857143

Iteration: 10

Cost: [[0.38716204]]

Accuracy: 97.85714285714285

Iteration: 11

Cost: [[0.35557885]]

Accuracy: 97.85714285714285

Iteration: 12

Cost: [[0.32788988]]

Accuracy: 97.85714285714285

Iteration: 13

Cost: [[0.30368962]]

Accuracy: 97.85714285714285

Iteration: 14

Cost: [[0.28254309]]

Accuracy: 97.85714285714285

Iteration: 15

Cost: [[0.26403564]]

Accuracy: 97.85714285714285

Iteration: 16

Cost: [[0.24779326]]

Accuracy: 97.85714285714285

Iteration: 17

Cost: [[0.23348834]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 18

Cost: [[0.22083889]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 19

Cost: [[0.20960497]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 20

Cost: [[0.19958386]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 21

Cost: [[0.190605]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 22

Cost: [[0.18252507]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 23

Cost: [[0.17522359]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 24

Cost: [[0.16859908]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 25

Cost: [[0.16256584]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 26

Cost: [[0.15705123]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 27

Cost: [[0.15199344]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 28

Cost: [[0.14733967]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 29

Cost: [[0.14304459]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 30

Cost: [[0.13906911]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 31

Cost: [[0.13537942]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 32

Cost: [[0.1319461]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 33

Cost: [[0.12874349]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 34

Cost: [[0.12574908]]

Accuracy: 98.57142857142858

Iteration: 35

Cost: [[0.12294312]]

Accuracy: 99.28571428571429

Iteration: 36

Cost: [[0.12030816]]

Accuracy: 99.28571428571429

Iteration: 37

Cost: [[0.11782877]]

Accuracy: 99.28571428571429

Iteration: 38

Cost: [[0.11549126]]

Accuracy: 99.28571428571429

Iteration: 39

Cost: [[0.11328345]]

Accuracy: 100.0

Iteration: 40

Cost: [[0.11119447]]

Accuracy: 100.0

Iteration: 41

Cost: [[0.1092146]]

Accuracy: 100.0

Iteration: 42

Cost: [[0.10733513]]

Accuracy: 100.0

Iteration: 43

Cost: [[0.10554823]]

Accuracy: 100.0

Iteration: 44

Cost: [[0.10384686]]

Accuracy: 100.0

Iteration: 45

Cost: [[0.10222465]]

Accuracy: 100.0

Iteration: 46

Cost: [[0.10067586]]

Accuracy: 100.0

Iteration: 47

Cost: [[0.09919528]]

Accuracy: 100.0

Iteration: 48

Cost: [[0.09777818]]

Accuracy: 100.0

Iteration: 49

Cost: [[0.09642027]]

Accuracy: 100.0

Test Accuracy: 93.33333333333333

Here's a neat observation. If a neural network is simple a two-layer network with non-linear activation, it is simply a matrix multiplication to new inputs. Therefore, we now have a way to learn that second-order probability matrix!

Given a neural network which can learn vector-vector relationships, it is easy to see that we can reconstruct our word-pair combinations from a vector that is the result of an attention step. Suppose we have a vector corresponding to the words 'My', 'rabbit', and 'likes', , the result of making it non-future-dependent is , and our attention step results in . We now pass this as input to a neural network and compute the output. The output will simply map our input vector to an output vector. The insight is that you can train the network to accurately map the result of our attention step to word pairs! The next obvious question is how to generate these word pairs. But before that, we need to notice that our neural network gets trained quickly when the input-output training sets have a small number of elements. It quickly becomes unwieldy when you think about practical languages, like the 260,000 Italian words mentioned above. This moves us on to our next topic, embeddings.

Embeddings

To make our neural network work well, we need a large amount of input-output data. This is impractical at the scale of even small, real languages - there are simply too many words. Generating one-hot encoding matrices by vertically stacking the vectors, even with techniques to store sparse matrices, is still impractical once we think about storing word pairs and triplets. We need some way to reduce these one-hot matrices in size so storing them becomes more efficient. This is the same problem we tried to solve with neural networks: converting an input vector into another vector. In our case, we want to convert a large vector to a smaller vector such that enough information is retained. This smaller vector will be called the embedding vector.

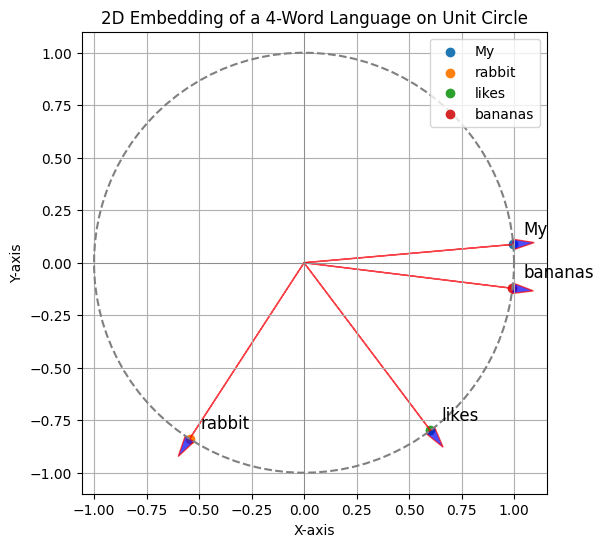

Based on all that we've seen so far, it is obvious that this conversion will be done with matrix multiplication. The question is how to make this new matrix. We can do the same thing we did before (training a neural network) or we can do something completely different. Here is an example. Suppose we want to embed 'My', 'rabbit', 'likes', and 'bananas' into 2 dimensions. We know that their one-hot encoding is an identity matrix, possibly with its columns shuffled. We can arbitrarily define a matrix that will project this matrix into a smaller matrix. We can then say that column 1 (representing, say, 'rabbit') of the initial matrix is now replaced by column 1 of the new matrix. This is perfectly fine. But is this meaningful?

What do we want from a 'good' embedding? Broadly, a good embedding should be useful for practical tasks. There is no use in embedding words and making the transformer's neural network harder to train. We might want to apply clustering algorithms to word embeddings to find out, for example, how many nouns there are in a large corpus (plural corpora) of text. We might also want to know what words are related in an unknown language. For someone trying to embed English, making sure that the embeddings for 'rabbit' and 'hare' are closer(i.e. their difference is closer to ) than the embeddings for 'rabbit' and 'desk' is important if training a model to explain what it says in pictures of lagomorphs in office environments. Embeddings should probably also capture context awareness - 'hot dog' must have a different embedding compared to both 'hot' and 'dog'. They should also not be too low-dimensional; we might lose important information.

It is beyond the scope of this tutorial to discuss good embedding algorithms. Fortunately, there is a straightforward algorithm we can use to embed our four-word language. Let's map them on the unit circle with a randomly generated matrix, as we have been doing so far.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

#define words

words=['My','rabbit','likes','bananas']

#ensure that the words are sufficiently apart for better visibility-say 30 degrees

angles=np.sort(np.random.choice(np.linspace(0,2*np.pi,360,endpoint=False),len(words),replace=False))

#compute unit circle coordinates

unit_circle_vectors=np.array([[np.cos(angle),np.sin(angle)] for angle in angles])

#define initial one-hot vectors

one_hot_vectors=np.eye(len(words), dtype=int)

#plot embeddings

plt.figure(figsize=(6,6))

for i,word in enumerate(words):

x,y=unit_circle_vectors[i]

plt.scatter(x,y,label=word)

plt.text(x+0.05,y+0.05,word,fontsize=12)

#draw the arrow

plt.arrow(0,0,x,y,head_width=0.05,head_length=0.1,fc='blue',ec='red',alpha=0.7)

# Draw the unit circle

theta=np.linspace(0,2*np.pi,100)

circle_x=np.cos(theta)

circle_y=np.sin(theta)

plt.plot(circle_x,circle_y,color='gray',linestyle='--')

plt.title("2D Embedding of a 4-Word Language on Unit Circle")

plt.xlabel("X-axis")

plt.ylabel("Y-axis")

plt.axhline(0,color='gray',linewidth=0.5)

plt.axvline(0,color='gray',linewidth=0.5)

plt.grid(True)

plt.legend()

plt.axis('equal')

plt.show()

# Print initial one-hot vectors and unit circle embeddings

print("Initial One-Hot Vectors:")

for i,word in enumerate(words):

print(f"{word}:{one_hot_vectors[i]}")

print("\nEmbedded Vectors on Unit Circle:")

for i,word in enumerate(words):

print(f"{word}:{unit_circle_vectors[i]}")

Initial One-Hot Vectors:

My:[1 0 0 0]

rabbit:[0 1 0 0]

likes:[0 0 1 0]

bananas:[0 0 0 1]

Embedded Vectors on Unit Circle:

My:[0.9961947 0.08715574]

rabbit:[-0.54463904 -0.83867057]

likes:[ 0.60181502 -0.79863551]

bananas:[ 0.99254615 -0.12186934]

Giving important to the position of words in a sentence while embedding text

Let's think a bit about our two-word non-future-dependent vectors. The only condition we have applied so far is that the value in the column matrix row wherever a word appears ahead of our current word should be 0. If a word appeared 1364 places before our current word but its value was deemed 'important' by attention, its corresponding row value would be 1. This is impractical. We know that it is unlikely that a word appearing 1364 places before the current word affects it. How can we quantify this?

The solution is to do it heuristically. Let's figure out what exactly the task is. We have to add some additional information in a word's embedding that denotes the position of the word in a sentence. This additional information is called the positional encoding. We want to satisfy a few criteria:

- The encoding must be unique for each word in the sequence even if that word appears again. The sentence 'My rabbit likes bananas but my friend's rabbit doesn't.' should have different encoding values for the first and second occurrences of 'rabbit'.

- If we have to add positional encoding to sentences of different lengths, the 'distance' between two pieces of information should remain constant. This means that 'My rabbit likes bananas. My friend's rabbit does not like bananas.' should encode the first and second occurrences of 'rabbit' in a way that the difference between the additional information added should be the same as the difference between 'likes' and 'does'. This ensures that the two sentences are recognized as part of a 'speech'.

- We should be able to generalize to any sentence length easily with bounded and deterministic values (i.e. do not train a neural network).

Essentially, we need to find a function whose codomain is a vector of the same size of the embedding that is:

- Easy to compute

- Periodic

- Has bounded values.

and iterate through the sentence, computing the function at the index of every word. To add the information to the word embedding, we can literally add the two vectors. This encodes positional information in the embedding.

A function that satisfies these criteria is

where is the number of rows in the column vector representation of the embedding vector, and are simply ways to denote even and odd positions (i.e. the first row of the encoding vector is a sine, the second row is a cosine, the third row is a sine, and so on) and . has been chosen completely by guesswork. simply denotes the row number. Another good property is that since the encoding are periodic functions, you have also put in some information saying 'the encoding of a word places away from the current word is so-and-so'. Their periodicity implies that they can be represented as a linear combination of earlier encodings. I want to reiterate that this is a heuristic that works and theoretical justifications for this do not really exist. It works because you have differentiated between sentences such as 'I just computed five times three plus two' and 'I just computed five plus three times two' which have different underlying meanings.

Converting embeddings back into words

We finally discuss actually choosing the next word in the sequence. Suppose that have taken a sentence, tokenized it, converted to one-hot encoding, embedded these encodings, added position embeddings, and then trained a neural network to predict an output vector. The final step is to convert this output vector, which is also an embedding, back into a vector that represents the target vocabulary. We do not want to convert it back into a one-hot vector. How will you choose the next word?

Let's do what is straightforward - multiply it with a matrix. This time, we are taking a smaller vector and making it a larger one. This comes with some caveats. We are making a column matrix bigger. If we want to make bigger, say to twice its size, how can we do it? Should we do , , or ? We can set up a matrix to do any one of these transformations, but we cannot set up a matrix that does this for all possible input vectors. This is because you will be solving an overdetermined system of equations. We have no choice but to accept this, so we have to assume that even if we find a matrix that makes the values as close to zero as possible, they will never all be 0 for any practical case. Going back to our initial task (English to Italian), we will end up with a vector that looks something like this

How do we select the next word? We can certainly pick the one with the largest value, but this is not so good. Fortunately, we have already looked at a way to emphasize the right word - softmaxing! Softmaxing and picking the highest probability allows us to enhance the probability of the right word (and it will be high because we train the neural network in this way - remember that matrix multiplications are just two-layer neural networks) being picked. An added bonus is that the softmax function is differentiable.

import numpy as np

#define words

words=['My','rabbit','likes','bananas'] #ensure vocabulary is 4 words long

print("Tokenized sentence:", words)

#ensure that the words are sufficiently apart for better visibility-say 30 degrees

angles=np.sort(np.random.choice(np.linspace(0,2*np.pi,360,endpoint=False),len(words),replace=False))

#compute unit circle coordinates (2D embeddings)

embedding_dim=2 #set embedding dimension to 2

unit_circle_vectors=np.array([[np.cos(angle),np.sin(angle)] for angle in angles])

#define initial one-hot vectors

one_hot_vectors=np.eye(len(words),dtype=int)

#function for positional encoding as defined in "Attention is all you need"

def positional_encoding(seq_len,d_model):

#initialize positional encoding matrix

pos_enc=np.zeros((seq_len,d_model))

for pos in range(seq_len):

for i in range(0,d_model,2):

pos_enc[pos,i]=np.sin(pos/(10000**(2*i/d_model)))

if i+1<d_model: #check to prevent index out of range

pos_enc[pos,i+1]=np.cos(pos/(10000**(2*i/d_model)))

return pos_enc

#calculate positional encodings for the sentence

seq_len=len(words)

positional_encodings=positional_encoding(seq_len,embedding_dim)

#calculate the sum of position encoding and embedding vectors

combined_vectors=unit_circle_vectors+positional_encodings

#decoder matrix to map combined vectors back to one-hot-like representations

decoder_matrix=np.linalg.pinv(unit_circle_vectors) #pseudo-inverse to decode

#decode the combined vectors

decoded_vectors=np.dot(combined_vectors,decoder_matrix)

#map decoded vectors to words by finding the closest match

def decode_to_words(decoded_vectors,word_embeddings,word_list):

result=[]

for vec in decoded_vectors:

#project vec back into the original embedding space

reconstructed_vec=np.dot(vec,word_embeddings)

#compute distances and find the closest match

distances=np.linalg.norm(word_embeddings-reconstructed_vec,axis=1)

closest_word_index=np.argmin(distances)

result.append(word_list[closest_word_index])

return result

decoded_words=decode_to_words(decoded_vectors,unit_circle_vectors,words)

#print initial one-hot vectors

print("Initial One-Hot Vectors:")

for i,word in enumerate(words):

print(f"{word}:{one_hot_vectors[i]}")

#print embedded vectors on unit circle

print("\nEmbedded Vectors on Unit Circle:")

for i,word in enumerate(words):

print(f"{word}:{unit_circle_vectors[i]}")

#print positional encodings

print("\nPositional Encodings:")

for i,word in enumerate(words):

print(f"{word}:{positional_encodings[i]}")

#print combined vectors

print("\nCombined Vectors (Embedding+Positional Encoding):")

for i,word in enumerate(words):

print(f"{word}:{combined_vectors[i]}")

#print decoded words

print("\nDecoded tokenized sentence from Combined Vectors:")

print(decoded_words)

Tokenized sentence: ['My', 'rabbit', 'likes', 'bananas']

Initial One-Hot Vectors:

My:[1 0 0 0]

rabbit:[0 1 0 0]

likes:[0 0 1 0]

bananas:[0 0 0 1]

Embedded Vectors on Unit Circle:

My:[0.1391731 0.99026807]

rabbit:[-0.5591929 -0.82903757]

likes:[-0.34202014 -0.93969262]

bananas:[ 0.89100652 -0.4539905 ]

Positional Encodings:

My:[0. 1.]

rabbit:[0.84147098 0.54030231]

likes:[ 0.90929743 -0.41614684]

bananas:[ 0.14112001 -0.9899925 ]

Combined Vectors (Embedding+Positional Encoding):

My:[0.1391731 1.99026807]

rabbit:[ 0.28227808 -0.28873527]

likes:[ 0.56727728 -1.35583946]

bananas:[ 1.03212653 -1.443983 ]

Decoded tokenized sentence from Combined Vectors:

['My', 'bananas', 'bananas', 'bananas']

Attention

We have technically made an encoder-decoder model at this point. As you can see in the code above, even without attention, it is somewhat difficult to get consistent sequence reconstruction. Let's think about attention again. So far, we have simply made an attention matrix and used it to suppress unimportant parts of the code. Our attention matrix was created by stacking one-hot encoded vectors on top of each other. This doesn't make much sense. Some parts of a sentence may be important - maybe not as important as other parts - but important nonetheless. Multiplication with an attention matrix should result in a vector with parts that are suppressed but not necessarily zero. We can give importance to different parts by making our attention matrix elements fractions instead of ones and zeros.

We have so far not defined precisely what attention does. We have so far said that given a matrix of attention masks, we can pull out specific rows given our one-hot encoded non-future-dependent vectors, and suppress things even more. Now we focus on the big question. How do we generate this attention matrix? We're in a completely different domain now - our words are no longer one-hot encoded, they're embeddings, we're adding positional information to them, and now we want to suppress irrelevant information.

Let's get an intuitive explanation of attention first. We can naturally ask whether the attention in machine learning is the same as attention in human beings. What does this mean? For example, our brain is flooded with many different sensory inputs every second. There's the internal sensory information from the body (such as level of hunger, blood pressure, pain, our balance), and there's external sensory information from the environment (such as me hearing the distant hum of cars outside the window while typing this, but choosing to ignore it). How do we not get overwhelmed? We 'tune out' (suppress) irrelevant information and only focus on the one that matters. Only a small subset of the sensory input data is considered relevant enough to be perceived - this is what we mean when we say we are paying attention to something.

Simply put, we are assigning importance to items by filtering out the irrelevant ones. We also have a finite amount of attention. For example, watching a group of ants move around is significantly easier than tracking the path of more than a few ants in that group. You can either have a general idea of how the group is moving, or a specific idea of how some finite amount of ants in that group are moving, but not both.

We can specify this mathematically: Given a set of input items , we assign nonzero weights to them, such that . Interpreting the weights as importances, they satisfy the two properties of human attention. We can than make a judgment about the items based on this attention. Since our inputs to the attention matrix are a collection of items (embedded word vectors), we can then assign a weight to them.

Where do these weights come from? This is where the learning in machine learning happens. We want to learn a function to compute these weights. This function is typically one that first computes some 'relevance' score for each word in the sequence and then softmaxes the weights in order to make the weights nonzero. We have already computed this relevance score. This is simply the sum of the embedding vector and positional encoding vector. What do we do now?

So far we have talked about second-order models. Throughout the tutorial, we have constructed our one-hot encoded vectors assuming second-order relationships in the past. We briefly said that we could extend the word-pair vector construction to word triplets, but as the discussion so far should show, this is very impractical. We now try to answer the question: How important is every word to every other word in the sentence, and it is possible to calculate this in one go? Positional encodings don't really answer this question, as they show how 'relevant' each word is in the overall sentence, but not in relation to the actual other words. We have to figure out three main things:

- How do you tell a word to 'ask' other words in the sentence the following question: 'How important are you to me?'?

- If this question is asked for every possible word pair, how do you calculate the response of every other word?

- If you are able to answer questions 1 and 2, how do you actually construct the vector that will be fed into the neural network?

Let explicitly define what this means. Each word has some sort of intrinsic value, which we have said is the sum of its embedding and positional encoding. For each word to ask each other word how important they are to it, we have to compare its intrinsic value to the other words' values. But what values? In the compound sentence 'I went out to buy fruit and my sister answered some emails.', 'fruit' and 'emails' are the objects of the subjects 'I' and 'my sister' in the two coordinate clauses. Even though they are very important within their own clauses, they are more or less irrelevant for the other clause. If there was an earlier relation such as 'my sister likes fruit' much earlier (say 1000 words behind 'buy fruit') in the corpus, it would make sense to compare the intrinsic values of the embeddings. But since we practically do not want to look 1000 words behind for all the reasons outlined above, it makes sense to assign each word a response value i.e. if asked a question by another word, the word being asked will return a response value that may be different from its intrinsic value. Based on what the response value is, the initial word will decide what information value it 'passes on' to the neural network so that it can reconstruct this efficiently. Also, it does not make much sense for 'I' and 'emails' to be compared, so you also have to figure out how much 'I' will pay attention to the other words. This triplet of intrinsic value, response value, and information value are what defines the attention process.

How do we make a word get a vector response from every other word? Like we have been doing all along, we define an attention matrix that is not one-hot encoded this time around. The attention matrix prepares each word for asking questions. Multiplying a word vector by this attention matrix results in a vector that contains the information 'how much attention should this word pay to other words?'. To make this process fast, you can stack each intrinsic value into a matrix and multiply it with the attention matrix. This results in a matrix (let's call this matrix ) that contains information about 'how much should every word pay attention to every other word'? Note that this is not pair-specific; we are not saying that 'I' should pay lesser attention to 'emails' than to 'went'. This is the behavior that is learned by the transformer.

Next, we multiply with a matrix that contains a matrix of responses of the other words. Like before, we are not explicitly telling 'I' to provide a worse response if asked 'How important are you to me?' by 'emails', but we are learning this behavior. Let's call the result of this matrix multiplication . You can now normalize the weights and softmax them in order for the matrix to have stable values. We then finally multiply this matrix by the matrix of information values to get the result of the attention step. This is the idea behind attention. contains information about how much weight each word should give to every other word, and contains information that makes our two-layer neural network make a judgment. These matrices are learned by the transformer by backpropagation.

Multi-head attention

Since we are now no longer dealing with nonnegative zero-one matrices, the question of how to do this calculation efficiently for large corpora still remains. Unfortunately we cannot. We can only rely on specialized and accelerated hardware. We are also still not sure whether the attention process actually captures meanings in a way that is human-understandable. The solution is straightforward: instead of having one set of matrices to perform attention, have more than one set. Apply each matrix set's attention independently, and for every newly returned information vector, combine them together in a specified way (usually, just concatenate, then use a neural network to predict outputs). The hope is that each set of matrices will learn something different about the text - sentence structure, word meanings, subject-object relationships. Each such set of matrices is called an attention head. To make this process somewhat computationally palatable, the matrices in multihead attention have smaller output dimensions (usually what the size would be for a single head for the whole corpus divided by the number of heads). In practice, this does work.

The final thing is dealing with practical languages. We still have to stack these attention blocks and two-layer neural networks many times in order to actually encode and decode things. This is the main reason it takes so long to train transformers on real text items. There is still of course the problem of getting correct datasets, but this is fine.

import numpy as np

tokenized_sentence=['My','rabbit','likes','bananas']

#combined_vectors is a np.ndarray of shape (4,2) that has been initialized in a different cell

intrinsic_value_matrix=combined_vectors.T

print("The intrinsic value matrix is:\n", intrinsic_value_matrix)

l=len(tokenized_sentence) #this is completely arbitrary - i want a machine learning model whose final dimension is 4

attention_matrix=np.random.rand(l,l)

print("The initial attention matrix is:\n", attention_matrix)

A=np.matmul(intrinsic_value_matrix, attention_matrix)

print("Preparing the words for attention, we get:\n", A)

response_matrix=np.random.rand(l,l)

print("The initial response matrix is:\n", response_matrix)

B=np.matmul(A,response_matrix.T)

print("The responses given by each word to each other word is:\n", B, "\n and after normalizing, we get:\n", B/np.sqrt(l))

B=B/np.sqrt(l) #explicitly rewrite the matrix

print("We will softmax the attention matrix in order to boost closer words. The result of doing this is:\n", np.exp(B)/np.sum(np.exp(B),axis=1,keepdims=True))

B=np.exp(B)/np.sum(np.exp(B),axis=1,keepdims=True) #store it again